|

February 22, 2007 | EPI Briefing Paper #184 A New Social Contract

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Elements of a new social contract. Americans who work hard should have a living wage, basic health and retirement security, and the tools they need to prosper in this new economy. . American workplaces and employment practices should support healthy and secure families rather than make workers choose between being productive workers and good family members. . In this increasingly unstable global economy, workers must have an adequate safety net that supports workers and families as they move across jobs and/or in and out of the labor force as their life and job circumstances change over time. |

How do we create these new family-sustaining labor market policies for the 21st century? There must be a resurgence of the roles that government, corporations, and labor unions played before the radical departure in the 1980s, roles that helped create the largest middle class in America's history.

Government's role in building a new social contract

The federal government has a critical role to play in ensuring that private institutions are structured in ways that serve the public's interests. With respect to work and employment, this means a government strategy and policy that ensure families and businesses thrive and prosper together. Since the New Deal, the American approach to meeting these obligations has been to enact minimum standards covering the essential rights and conditions that all employees should be guaranteed and to develop administrative actions that support worker, union, and employer efforts to gradually improve on these minimums as economic conditions allow and social conditions warrant.

Government's role is also to ensure that workers have the tools, including the necessary skills and supports, needed to contribute to and prosper in the modern economy. A third task is to support workers and families as they change jobs in this unstable economy or go in and out the labor force or between full- and part-time jobs as their family and life circumstances change over time.

How can government carry out these responsibilities in ways that reflect the features of the contemporary workforce and economy? There are seven broad areas in which government can play an active role.

1. Macroeconomic policies that support good jobs

Creating and sustaining good paying, high quality, knowledge-based jobs has to be an on-going top priority of any family-centered labor market and employment policy. A strong jobs agenda requires a combination of efforts, starting with a strong macroeconomic policy that promotes sustained economic growth and job creation. Without this, all other micro or specific job creation or training and education initiatives are likely to fall short of their objectives.

Since 1946 the nation has been committed in principle to a full-employment policy. Every politician from Harry Truman to George W. Bush has proclaimed, "I won't be satisfied until every American who wants a job can find one."1 But in reality, macroeconomic fiscal and monetary policy have given higher priorities to controlling budget deficits, inflation, and taxes than to job creation and full employment. Indeed, the current recovery has recorded the slowest rate of job growth of any period of economic expansion since World War II. Rebalancing national priorities to give full employment equal billing to these other objectives is essential to ensuring all who want a job can find one.2

2. Trade policy

As foreign trade has grown dramatically, the U.S. government's global policies have been counterproductive to the interests of everyday Americans. There has been a "race to the bottom" in how workers are treated in the name of global competition. In order to stop such a race, standards must be enforced that reflect the nation's shared values. The International Labor Organization, a tripartite labor-business-government agency of which the United States is a part, has already approved a group of core worker rights. These include freedom of association; the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labor; the effective abolition of child labor; and the elimination of discrimination in respect to employment and occupation.3

These core labor rights should form a minimum basis for global trade and should be enforceable in any trade agreement in which the United States takes part. Without standards, global competition will merely be a race to the bottom that encourages the worst forms of human practices. These will hurt not only workers in less-developed countries who are forced to work under those circumstances, but also American workers forced to compete at that level. This is merely the beginning. The objective is to have a global policy that benefits everyday working Americans and their families.4

3. Living wage

A bedrock principle of a modern labor market policy must be to ensure that all who work earn a living wage. America has failed to meet this standard for many years. Instead it has relied on increased hours of paid work contributed by wives and mothers over the past two decades as the safety valve that kept society from imploding. The challenge facing the economy and families today is that there are no more hours available to further advance family income. Wages simply have to rise. This is particularly true for those at or near the bottom of the wage distribution.

Two government policies, the minimum wage and the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), affect wages and family incomes of those at the bottom of the wage and income distribution. These are now widely recognized as complementary policy instruments for raising the real incomes of low-wage workers and their families. The federal minimum wage languished at $5.15 per hour for 10 years between 1997 and 2007. The value of the minimum wage during that period was at its lowest level since 1955.5 In 2007, Congress will likely raise it to $7.25 per hour. Yet $7.25 still does not restore what it would have been if it had just kept pace with its peak in purchasing value in 1968. In order to do that, Congress needs to gradually increase it to $9.00 per hour and index it to ensure that it does not lose purchasing power in the future. These changes would help those at the bottom and make a small but substantive contribution to reducing the widespread wage inequality in America.

Those who argue against raising minimum wages often claim that a raise will reduce demand for entry-level, low-wage workers. The empirical evidence, however, establishes that moderate increases have little if any negative employment effects.6 Obviously, if the minimum wage were pushed up too high, it would have this effect. However, it has been nearly a decade since the last increase—a gradual increase to $9.00 an hour would clearly fall short of this threshold.

The EITC complements the minimum wage in two ways. First, it further increases income without negative employment effects because it reduces (or eliminates) income taxes on earned wages rather than increasing the wages employers pay. Second, it is linked to family needs by being graduated for the number of people in one's household. Combining increases in the minimum wage with increases in the EITC would help working families achieve incomes that move them out of poverty and start them on the way to earning a decent family wage and moving up the economic ladder.

Government should also play a role in encouraging corporations to create family-sustaining jobs by requiring firms that do business with or get benefits from a city, state, or the federal government in the form of subsidies, contracts, tax abatements, or other ways to pay living wages and provide basic benefits. Today, there are more than 130 living wage ordinances around the United States.7 This government strategy would help change the strategies of many companies who choose to maximize profits by cutting wages and benefits and investing little in their workers. This is beneficial for not only the workers and their families, but also for taxpayers and society. When companies pay low wages and few benefits, taxpayers pick up the costs through government subsidized programs.

4. Health care and pension benefits: firm-centric or portable benefits

Pension and health care coverage are declining and the financial security and health care risks and costs are increasingly being shifted to workers and their families. Employer-provided health insurance covered 69% of workers in 1979 compared to 56% in 2004.8 The number of workers covered by pension plans has dropped by 5% between 1979 and 2004. But more important, the kind of employer plans provided by employers has radically changed. Defined-benefit plans covered nearly 40% of workers in 1970 and now cover less than 20% of the workforce.9 Moreover, the shift from defined-benefit plans to defined-contribution plans (really, savings plans with special tax advantages) has put the burden of retirement directly onto the worker. Those who have the resources to put money into these plans get tax advantages, but most everyday working Americans do not have the income to save.

This laissez-faire benefit model has failed. Without government defining some basic standards for health care and pension benefits, the number of Americans without health insurance will continue to rise and retiring Americans will be without the needed resources to have basic dignity at the end of their working lives.

America needs a set of health care and retirement standards that fit today's economy and workforce. The architects of the New Deal designed a set of health care and retirement provisions based on the assumption that most workers would be employed in a long-term, relatively stable employment relationship. Because workers were expected to stay for long periods of time with a single employer, it seemed sensible to link provision of benefits to a specific employer. Moreover, because workers were assumed to be classified as employees under employment law, they would be covered by the full range of legal protections and funded benefits tied to specific employers.

Today's reality differs dramatically from this idealized view of work and employment relationships. The roughly 17% of the labor force classified as temporary workers or independent contractors are now largely excluded from coverage or access to these labor standards and benefits.10 Moreover, employment duration is becoming more uncertain and has declined significantly for young workers and men of all ages.11 Finally, firms that in past years have met the expectations of the old social contract now find themselves at a competitive disadvantage to younger firms and international competitors that are not carrying the costs of health insurance and pensions for long-service employees and retirees.

Step by step, the firm-and-tenure–based labor market strategy for funding financial security is being undermined. America needs to gradually move away from its dependence on individual firms to deliver certain labor market benefits and services.

Health insurance and pensions are obvious places to start the shift from employer-centric to more portable, universal coverage options. Employers would still have a role in helping fund these benefits, but how they are delivered needs to be adjusted to ensure coverage for all working Americans. This would also level the playing field for those companies that provide benefits with those that refuse to do so. Numerous proposals have been put forward for how to either replace or, more realistically, how to complement employer-provided health insurance.

One pragmatic and creative option that we believe fits well with the other elements of the new social contract discussed here is called "Health Care for America,"12 which would create a public insurance pool linked to Medicare to cover those not insured through an employer-provided plan. Employers would have a choice to either pay into the public fund or substitute their own equal or better health insurance for the public plan if they prefer. Employees would pay premiums to the public plan and non-employees would be required to purchase coverage on an income-based scale. Other options are being tried at the state level. Massachusetts, for example, has introduced a program that requires individuals to purchase health insurance and employers to either provide coverage or pay a small annual fee. California is considering a slightly different approach.

Similar ideas are being put forward to close the gap in retirement savings that is building up at an alarming rate as defined-benefit pension plans are abandoned or frozen. Proposals for universal and fully portable 401(k) plans, universal savings accounts, and other hybrid solutions are being developed that are essential in addition to an expanded and strengthened Social Security.13 There is no need to discuss the advantages and disadvantages of each of these here. America cannot rely on individual workers alone to have the means to fund pension plans. Most working Americans simply do not have the resources. Corporate America must be held accountable for its obligation to help fund plans that move with employees across jobs throughout their working lives.

From our workforce and labor market perspective, the key design feature for both health care and pension reforms is that plans should be fully portable. Most important, however, is that the plans provide health care coverage to all working Americans and their families and that workers, at the end of their careers, have the needed resources to retire with basic dignity.

5. Family-centered labor market policies

Building a new social contract that fits today's economy also requires that we recognize the seismic shifts in both families and the workforce that have taken place since our basic employment policies and institutions were put in place. Most policies and institutions were designed to serve the 20th century's industrial economy and a workforce dominated by a male breadwinner with a wife at home taking care of family and community responsibilities.14 The trends have changed dramatically in recent decades:

• Today three-fifths of women age 16 and over are in the paid labor force, as are 70% of mothers with children under 16 years of age.

• Only 21% of married families fit the old "male breadwinner" model with the husband in the labor force and the wife at home, compared to 56% in 1950.

• Single parents now account for 10% of all households, up from 8% in 1979.

• Wives have increased their working hours by one-third to one-half between 1979 and 2004. The largest increases (535 hours or just under three months) have come from wives in middle-income families. As a result, middle-income families with children now work approximately 3,500 hours per year, close to the equivalent of two full time workers. This is an increase of about 18% since 1979.15

• Increased earnings by wives since 1979 accounted for all of the growth in real family incomes for families in the bottom two-fifths of the labor force and for about 80% of the growth in middle-income families.16

• More than 20% of households report being responsible for some or all of the care of elderly relatives. These percentages are expected to double in the near future as the population ages.17

These facts illustrate how tightly coupled work and family activities are today. Government must play a role in this modern workplace to set minimum working conditions and rules and provide the supports necessary to ensure that Americans can be both productive and successful workers and good parents and community citizens.

Meeting this standard will require flexibility and resources. Many firms are already providing flexibility to their professional and managerial employees who work on a salaried rather than hourly basis. But these "family friendly" benefits are seldom accessible to those in the lower half of the wage and occupational distribution. Today, 50% of America's workers do not receive one paid sick day. Three-fourths of low-wage workers suffer the same fate. So America's parents must choose between losing a paycheck or their job and taking care of a sick child or responding to a family emergency.18 The same opportunities to take time off afforded the majority of salaried and professional employees need to be extended to workers across the full occupational and wage distribution.

The Healthy Families Act introduced in Congress by Senator Edward Kennedy and Representative Rosa De Lauro, which would require employers to provide seven paid sick days a year to all employees, is the right kind of response to this issue. It is the kind of minimum standard that would make it possible for all parents who work to have the needed paid time off for their own or their child's illness without the fear of losing their wages or their jobs.

Most everyday workers face the same dilemma when they give birth to a child or face a serious illness of a loved one. The federal Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), passed in 1993, was a good first step in creating a workplace for the 21st century. The FLMA gives workers the right to take unpaid leave upon the birth or adoption of a child or in case of serious illness. However, more needs to be done. Many everyday American workers just cannot afford to take this leave. They face the Hobbesian choice of giving up wages that are needed to pay for care for their newborn or giving up the time to be with a newborn in their first days.

That is why nearly every other industrialized country provides some form of paid family leave for workers at all levels. It is time for America to catch up. California is showing the country one way to do this with an employee-funded model. While the California plan is an important first step, the United States needs to move to a more comprehensive federal model that provides for paid family leave for all working families.

Today, nearly three-fourths of mothers with children under 18 now work outside the home. Most other nations have responded to the increase of women in the workforce by ensuring that children receive adequate care. But the United States has lagged in this area. Unlike other nations, the United States has done little to ensure that, while America's parents are at work, their children receive the care they need. Today, it is up to the individual parent to provide whatever resources are necessary. But most workers cannot afford the quality child care and early education needed by their children. This sets up a two-tiered system in which the children of the wealthy get the care and education they need, while the children of most Americans do not.

Today government provides for public education from kindergarten to 12th grade. It must update its response to today's workforce and the needs for children's educational development by providing affordable quality child care and prekindergarten. Many states, including Georgia and Oklahoma, already provide universal prekindergarten and the U.S. military has one of the finest examples of government-provided child care. America also needs to ensure that there are proper after-school programs so that parents can work knowing that their children are in quality educational programs.19

These are only minimum standards. But like the minimum wage and other standards enacted as part of the New Deal, the goal would be to initiate a gradual expansion of flexible employment practices across the economy that fits the specific business and family needs of different workplaces. Employees, supervisors and managers, and unions need to discuss how to do so. In some cases, the best way to achieve the needed flexibility may be to change work schedules. In other cases, changing how the work is done may be part of the solution.

Britain has recognized the value of these types of conversations and workplace-specific approaches to flexibility. Since 2003 workers in Britain have a legally protected right to request flexible work options and employers have an obligation to make reasonable efforts to accommodate their workers' needs. In the first year the law was in effect 25% of those eligible made a request for flexible hours or schedules and over 80% of the requests were accommodated.20 This is the type of cooperative workplace dialogue that workers have been calling for in the United States for many years. The work-family arena would be an ideal laboratory to test whether American employers and employees can make such a policy work to the mutual benefit of their businesses and their families.

These same types of conversations also need to go on at the community and state level among business, government, community, education, and labor leaders. Individual firms, acting alone, cannot resolve all the challenges to integrating work and family life. School hours, after-school programs, community day-care providers, welfare-to-work training, and income support programs all intersect with workplace practices to affect the ability of single and dual income parents to manage their work and family responsibilities. Massachusetts is about to lead the way in creating a Work-Family Council to coordinate the actions of these different institutions. Similar groups should be encouraged in all states and communities.

The sections to follow will show that other complementary changes in labor market policies and institutions will be needed to build a truly family-centered employment system. The key point here is to not pigeon-hole "work-family" issues either as the special domain of women or narrowly focused on firm-based "family friendly" initiatives or to treat them as a private matter apart from workforce and employment policy issues. Instead, as shown throughout this briefing paper, the close interdependence of work and family obligations needs to be built into the updated designs of all policies, institutions, and practices governing work.

6. Providing the tools for working in the New Economy

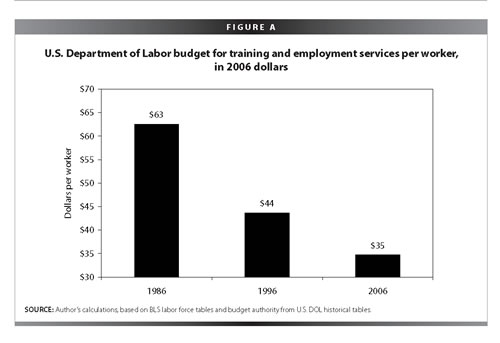

America cannot aspire to be a knowledge-driven economy if it fails to invest adequately in keeping the skills and knowledge of its workforce current. Yet instead of increasing funding for training so that America's workers can be competitive in this global economy, the United States has decreased spending. Expenditures for training and employment services by the U.S. Department of Labor, the nation's primary agency responsible for funding training, have declined from $6.1 billion in 1986 to $5.2 billion in 2006. Figure A puts these numbers in perspective: given growth in the labor force and prices over this time period, the Department's investment in training and employment services fell from $63 per worker in 1986 to $35 per worker in 2006.21

In comparison to other OECD countries, the United States lags in investing in active labor market policies (employment and training, job creation and placement, etc.), ranking 25th out of 26 countries in the percent of its GDP devoted to labor market programs. 22 As a nation, it is time to put our money where our mouth is and budget for continuing education and training in ways needed for workers to keep their skills current.

Even with increased funding, public resources must be used wisely. One way to get the most out of government funds is to use them to leverage and complement private sector efforts. The overwhelming consensus of labor market specialists is that training pays off the best (in terms of job placement and earnings) when workers and training programs are embedded in networks that link workers wanting to improve their skills with employers in need of well-trained workers.23

Over the years the institutional architecture to support this approach has been created.24 The most recent incarnation of this approach is embodied in community and regional Workforce Investment Boards composed of industry, government, labor, and community representatives. The best of these boards work with a growing variety of "intermediaries" that match specific groups of workers with employers.

Unfortunately, the Bush administration has chosen to ignore the evidence regarding the importance of networks and institutional cooperation by shifting resources largely to individual short-term training vouchers. This is a poor use of scarce federal resources, given other evidence showing that longer-term training programs that take into account language, cultural, and family needs have higher payoffs than short-term, narrowly focused training programs. It is time to build on what we know works and focus federal resources on expanding the networks that link workers with the right mix of skills to jobs ready to be filled.

Another role for government is to overcome the market failures that inhibit investment in general skills by private sector firms. Firms invest significant resources in training their employees for the specific jobs and technologies relevant to their organizations. But it has long been recognized that individual firms are reluctant to pay for general training unless their labor and product market competitors do the same. This generates a market failure and an underinvestment in the types of life-long learning workers need to keep their skills current and competitive in the external labor market. This market failure can, however, be overcome by encouraging and supporting unions, professional associations, community colleges and universities, and other intermediary organizations, individually and in partnerships with employers, to become suppliers of life-long learning.

Some are already doing so. The Communication Workers of America has been a leader in promoting life-long learning through jointly negotiated, funded, and administered education and training programs. Similar joint workforce development programs are funded through collective bargaining in the auto, steel, aerospace, health care, hospitality, and other industries. Craft unions in the construction and entertainment industries have well-established apprenticeship and other training programs. Many professional associations provide continuing education courses that meet the requirements members have for maintaining their credentials. But too many of these are grossly under utilized as a source of continuous, life-long learning. Many workers lack the resources and time to participate.

These private sector models need to be expanded and supported and seen as part of the critical infrastructure of an active labor market policy. Government should encourage these programs by providing human capital investment tax credits or other incentives to support their expansion. The more these programs grow, the more competitive labor market pressures will lead individual employers to support them.

7. Unemployment insurance

Too often debates over labor market policies are framed as a trade-off between flexibility and security. The American labor market is often viewed as being highly flexible since employers can—and do—layoff or discharge workers "at will." In contrast, the stereotypical view is that European labor markets give priority to security over flexibility by making it more difficult for employers to layoff or discharge permanent workers. In fact, this is a false dichotomy.

The best performing OECD economies and labor markets such as Denmark, the Netherlands, and Norway have fashioned what they call "flex-curity" labor market policies that are as flexible as those in the United States but that provide the training, job referral, broad-based unemployment insurance, and other services needed to support a mobile workforce. 25 These economies receive high marks from workers for the long-term employment and financial security they provide and from employers for their flexibility and the competitiveness of their firms.26 America can learn from these policies.

America's unemployment insurance system was designed to provide income supports to workers laid off temporarily from a long-term job. Laid-off workers had a reasonable expectation of being recalled when business conditions improved. Moreover, because workers were assumed to be classified as employees under employment law, they would be covered by the full range of legal protections and funded benefits tied to specific employers.

Today's unemployment is dramatically different. Those laid off are more likely to be permanently rather than temporarily displaced and many workers can no longer find jobs in the industries in which they worked. When a recession ends, it is harder for laid off workers to return to good jobs. Many who are looking for full- or part-time work are new entrants or re-entrants to the labor force. A substantial number of people out of work do not qualify for unemployment insurance because they were previously employed in non-standard or part-time jobs. As a result, only about 37% of the unemployed have received unemployment insurance in recent years.27

The changing nature of unemployment and of the unemployed requires a major overhaul of state unemployment insurance programs and federal programs that respond to national trade policies and economic contingencies. It is time America updates its unemployment policies to look more like re-employment policies that respond to today's realities.

Four sets of reforms are most critical at the state level. First, coverage needs to be broadened to include those entering or reentering the labor force, those working or looking for part-time work, and those in non-standard jobs. Second, workers should be allowed to enroll in training programs of sufficient duration to make a difference in their market power without losing benefits. Third, the policy of linking eligibility to tenure with a specific employer should be changed to an hours-of-work criterion so as not to penalize those who work for short periods of time with multiple employers. And fourth, workers who are between jobs must be assured health care coverage for themselves and their family and the needed supports such as home loan assistance to preclude major economic dislocations.28

At the federal level, there has been a recognition that a society that wants to enjoy the benefits of an open and fair trade policy must, out of fairness and practical politics, help workers and families who bear its costs. Building broad-based political support for trade policy will require going beyond the presently structured Trade Adjustment Assistance program (TAA) (a program that provides limited income supports for workers who can show they lost their jobs because of increased imports).

TAA is the commitment that America will provide wage and health benefits while trade-displaced workers retool, retrain, and find better jobs. Yet today, even though eight out 10 American workers are in service professions, TAA only applies to workers who make a product. This must change. TAA must also increase funding to provide retraining and eliminate the arbitrary training restrictions, make health care coverage truly affordable to covered workers and their families, and apply TAA to all workers displaced by trade, not just those affected by free-trade agreements. In fact, the United States should seriously examine the idea of expanding TAA into "GAA"—Globalization Adjustment Assistance that would offer benefits not only to workers displaced by trade, but also to those displaced by all aspects of globalization.

The federal unemployment system must also have greater capacity to respond when recessions hit. In recent years, there have been record rates of long-term unemployment and numbers of workers exhausting their state benefits. The United States needs an effective and reliable federal program that has a permanent extended unemployment benefit that would take effect when unemployment levels and the number of workers in states who exhaust their state unemployment benefits reach a certain level. Ultimately, Americans may want to look at one federal/state unemployment system that ends the debate on the cause of job loss and has a comprehensive approach to respond to the volatile economy that produces large job losses on a continual basis.29

Other unemployment proposals have also been put forward. One idea is wage insurance. Wage insurance would make up part of the difference between the wages of a job lost and the wages earned on one's subsequent job. The motivation for this proposal stems from data that show many workers—especially older, long-tenure workers displaced from good paying manufacturing jobs—experience significant and often permanent wage reductions.30 Wage insurance seeks to make up some of this difference.

Wage insurance, however, raises serious concerns about providing subsidies to low-wage employers and discouraging retraining. Thus, it runs counter to efforts to encourage firms to create and sustain good paying jobs. It may be useful on a very limited basis in supporting older workers who have been laid off after long years of service with their employer and do not have sufficient time to be retrained, but it is no substitute for the more basic reforms described above.

Corporations' role in building a new social contract31

American corporations must also be required to do their part to put in place a new social contract that works for their shareholders, employees, and customers and helps them transition to a knowledge-based economy. As a part of this effort, corporations must treat employees and their human capital as a company's "most important assets" rather than costs to be minimized and controlled. The latter view carries over from the 20th century corporate models in which financial capital was the dominant source of competitive advantage and corporations were viewed primarily, or in some people's minds solely, as instruments for maximizing the wealth of its financial investors.

The view that corporations need only serve the interests of their shareholders shifted after WWI, largely through the countervailing power of unions. Corporate executives understood that if they veered too far in favor of shareholders at the expense of workers and their communities, they would experience a backlash—workers through their unions, would demand their fair share of corporate profits. But as unions declined so did the countervailing pressures to share profits and productivity with employees.

Gradually, the pressures from Wall Street began to overtake pressures from Main Street. By the early 1980s—as the era of hostile takeovers, leveraged buyouts, and excessive use of stock options and other executive compensation schemes designed to reward CEOs for focusing exclusively on maximizing shareholder value took hold—it looked like Wall Street was all that mattered to CEOs.

This shareholder-primacy model of the firm was reinforced by employment strategies designed to minimize and control labor and other factor costs and avoid anything that would limit management's freedom to allocate and move resources (including jobs or people) to their lowest cost environments. This intensified efforts to keep labor in check by avoiding unions or where present, holding them at arms length to minimize their influence in collective bargaining and in strategic decisions. By doing so, managers could move work around the world to whatever locations offer the lowest labor costs and fewest constraints on corporate decisions. The popular literature refers to this as the "low road" or "race to the bottom" strategy.

Fortunately, a resurgence of the view of the corporation as having responsibility not just to shareholders, but also to employees and all stakeholders is slowly beginning to gain acceptance. This resurgence has been fueled in part by corporate scandals, CEO pay levels that have continued to escalate while the compensation of non-management employees' wages has stagnated or declined, and the significant increase of outsourcing and off-shoring of jobs. The more accountable corporate model views the corporation as a team requiring the investment and full commitment of assets that workers, investors, and managers bring to the enterprise.32 This view argues that corporate leaders should be held accountable for maximizing the total value of the firm and protecting its long-term viability for both workers who invest and put at risk their human capital and also investors who commit and risk their financial capital.

To do so, the firm needs to adopt strategies and employment practices that build and sustain the trust and long-term commitment of its human and financial investors and return fair value to both groups. Those who participate in governing the firm need to be held accountable for creating value, investing for a sustainable future, and distributing fairly its proceeds to the constituent groups that help create it. This implies that all groups should have a voice in choosing and holding accountable members of corporate boards or other governance bodies.

This alternative view of the firm is based on the argument, supported by a large body of evidence, that there is a high- productivity and high-wage employment strategy that can be successful if firms invest in their people and engage them in the search for productive and innovative ideas and ways of serving their customers. (The popular literature labels this the "high road" strategy.)33 While the specific ways to implement this strategy vary across industries and occupational groups, their common features include selecting well-educated and prepared workers, investing in on-going training and development to keep workers skills current, paying good wages and benefits to retain workers and keep turnover costs down, and organizing work processes and systems to make full use of workers' individual and collective knowledge, creativity, and problem-solving abilities. To maintain support for this approach, the gains produced need to be shared fairly among shareholders, customers, and workers.

Which view of the corporation and which strategy will win out? There are no guarantees. Today there are examples of firms in the same industries that compete based on both strategies and produce the results predicted. The problem is that the institutional and policy environment in the United States is biased to encourage the low road and inhibit the high road.

Consider Wal-Mart, America's largest employer.34 Wal-Mart grew to this size and status by focusing on one thing: having a lower price than any of its competitors. To many, this is a great American success story. Tell this, however, to the communities that have experienced a net job decline, neighborhoods that have lost a host of small businesses, and employees pursuing Wal-Mart in class-action suits for gender discrimination, violating wage, hour, and labor laws, and shifting the costs of its employees' health care to state governments.

Most recently, the company made its strategy even more explicit by implementing new pay caps on long service employees, increasing use of part-time workers, and requiring workers to be on call and available as needed. When various commentators compared Wal-Mart's role in the economy to the role played by General Motors in the 1950s when it was the largest employer, Wal-Mart's answer was—we are in retail and cannot be expected to be a wage or benefit leader. This was their excuse for breaking unions, pressuring store managers to cheat workers out of overtime, and locking employees in their stores at night because they did not trust them not to walk out with the store's merchandise.

Americans should and can expect more from its largest employers, even in industries as competitive as retail. Other retail firms such as Costco have demonstrated they can pay decent wages and benefits, respect workers' rights, and be profitable. When they do so, however, some on Wall Street complain they are being too good to their workforce.

Or consider the airline industry where service deteriorates while employees watch their wages get cut, the government has to take over responsibility for pensions in default, and the major network carriers lack a business model that can produce profits, good customer service, and good jobs and careers.

Again, we know there is a better way. Southwest Airlines has shown how to manage an airline through these turbulent times by treating employees as family and respecting their rights to be represented by labor unions.35 Continental Airlines learned the hard way that simply using the protection of bankruptcy to cut labor costs and void their union contracts was not a successful strategy or sustainable path to recovery. Only after a new management team at Continental took over in 1994 and began working with its employees and unions did it get back on a path to recovery.36 Other airlines should learn from Southwest and Continental how to provide decent service at reasonable prices through a fairly paid and committed workforce.

In nearly every sector of the economy, some firms have learned how to build knowledge-based work systems and organizations that draw on the skills and motivations of their employees, structure work to encourage problem-solving and innovation, share information, and treat employees with respect. These approaches have demonstrated their ability to produce high levels of productivity, customer service, and profits. They are the features of the 21st century knowledge-driven workplaces that our schools and colleges are training young people to enter and to expect.

For the high road model to become the norm, corporations need to be held accountable for serving not only the interests of their shareholders, but also the interests of their employees and families. The guiding principle should be that employees who invest their human capital in businesses should have the same rights to information and voice in corporate governance as those who invest and put at risk their financial capital. To ensure this worker voice, corporations should be required to have at least one director on their boards that represents worker interests.

Since society has a stake in corporations pursuing the high road model, government needs to enact and enforce labor laws that punish low road behavior, and support investments in human resources the same way it supports investments in research and development and technology. Firms must be held accountable for meeting minimum labor standards wherever they locate production or purchase goods and services from suppliers. This will require negotiating labor standards directly in trade agreements and working with NGOs, national governments, and global corporations to enforce both codes of conduct now on the books of numerous firms and national laws governing labor standards.

Moreover, the government should permit corporations to receive taxpayer dollars in the form of subsidies, tax breaks, and contracts only if they comply with labor and employment laws and regulations and provide family-sustaining jobs. Taxpayer dollars at the national, state, and local levels should not subsidize corporations that fail to respect their workers' basic rights and interests.

A forward looking government policy should also help employers and industries learn what it takes to compete successfully and to promote high road strategies. The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation has formed 25 industry-university research projects to study, document, and diffuse practices and strategies that help firms be competitive while providing good jobs and wages.37 The projects are a model for how government policy makers could institute high road practices at the regional and industry levels of the economy. By doing so, the learning and diffusion process might someday get to the point that even Wall Street gets it. But history proves that widespread diffusion of business strategies and employment practices that can support a new social contract will also require a strong voice for Main Street America. That is why the third pillar for a new social contract is a modern, 21st century labor movement.

Labor unions' role in building a new social contract: A labor movement for the 21st century

Throughout much of the 20th century, millions of American workers could count on the labor movement to provide them with a voice at work and to be a powerful force for working families in social and political affairs. It was instrumental in building the strong middle class of post–World War II America. As union membership and power declined, the norms that kept wages, productivity, and profits moving in tandem lost their force.

Now, as rising income inequality and the failure of wages to move with productivity are being noticed, America is beginning to recognize the economic and social costs of a severely weakened labor movement. To build the next generation unions and to unleash their innovative potential requires a labor policy that protects workers rights to organize and encourages the forms of labor-management relations that work for a modern economy.

1. Reforming and modernizing labor policy

Society has a keen interest in a strong, independent, and innovative labor movement. We know what unions bring to workers in terms of living wages and basic benefits and a voice in their workplace. Unions raise the wages of their members by roughly 20% over those of their non-unionized counterparts. In traditionally low-wage jobs, home-health-care workers, child-care workers, janitors, security guards, food processing, and hotel workers, the increase is 27%.38 With regard to benefits, 86% of union workers are covered by health benefits through their employer in contrast to 59% of non-union workers. Unionized workers are also 54% more likely to have employer-provided pension plans.39 Unions are essential to bringing a voice for the needs of everyday Americans to the political debate.

A modern labor policy therefore needs to both ensure that workers have access to union representation and also encourage the forms of representation and labor-management relations best suited to today's workforce and economy. This is not the case today and has not been the case for a very long time.40 Consider, for example, the stark realities facing workers who try to exercise the right to join a union promised them in the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA):

• In 2005 the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) awarded over 33,000 workers either back pay or reinstatement because they were illegally fired or disciplined by their employer for exercising their right to form or participate in a union.41

• The chance a union supporter or activist would be fired for attempting to organize rose in the 1980s compared to the 1950s through the 1970s, then declined somewhat in the late 1990s and once again rose between 2000 and 2005. Today about two of every 100 union supporters get fired for exercising their legal rights. Those who actively campaign in support of their rights face substantially higher odds of discipline or discharge.42

• Recent analysis shows that only 20% of organizing drives end up getting a labor agreement. If an employer resists by committing an unfair labor practice—firing union supporters for example—the chance of getting a labor agreement goes down to under one in 10.43 Even in cases where a majority votes to be represented by a union, there is only a little more than fifty-fifty chance (56% to be exact) that workers will get a first contract.

• Today there is a booming business for union avoidance consultants. Firms hire and devote resources to these consultants in over three-fourths of all organizing campaigns.44

• Employers have lobbied Congress and the NLRB to outlaw use of card check recognition even though the evidence demonstrates that workers experience less stress and conflict and gain just as much information to make an informed choice in card check processes as is the case in contested elections.45

• Recent surveys show that about half of the non-union workforce would join a union if given the opportunity to do so. This number is up from about one-third of the workforce in the 1970s.46 So a growing number of workers want representation but have no way of gaining access to it, given the current structure and enforcement of labor law and union organizing strategies.

• Surveys from the 1970s through the 1990s have also shown that about 70% of the workforce want management to cooperate with workers and unions in providing a voice at work.47 This is another sign of the representation gap American workers now experience.

These are indicators of a failed policy. America is effectively denying workers a voice at work, contrary to our democratic norms, stated public policy, and widely shared values and expectations of the American public. Indeed, the failure of labor law to protect workers' right to join a union free of employer coercion is one of the major causes of union decline. The result is a declining middle class, and the loss of everyday Americans' ability to have a piece of the American Dream.

Rebuilding worker voice will therefore require significant reform and updating of current labor law. The policy reforms need to be both remedial and forward looking. The remedial reforms must start by eliminating fear, delay, and illegal conduct from the beginning of the organizing process through to the successful negotiation of an initial labor agreement. An Employee Free Choice Act has been introduced in Congress by Senator Ted Kennedy, Congressman George Miller, and a large number of co-sponsors that would address these issues by allowing for card check recognition, shortening the time period for representation elections, strengthening penalties for illegal actions, and providing for arbitration of first contracts when necessary.

These and other reform proposals need to be able to enforce a simple and clear principle: Any worker who wants to join a union and be represented should be able to do so free of intimidation, coercion, or managerial interference. Gaining access to union representation should be easy, quick, and safe, not hard, slow, and risky.

These reform proposals all stay within the basic NLRA doctrines and seek to ensure those doctrines are implemented effectively and fairly. They serve as a necessary but not sufficient step for updating our labor relations system. Labor laws need additional modifications to provide access to representation to the broad range of workers who are excluded from coverage either because they do not fit the increasingly restricted definitions of an employee covered by the law or have little hope of ever achieving the majority status or exclusive representation in a defined bargaining unit as deemed necessary to negotiate labor agreements under the current law.

There is increasing recognition that labor law has become ossified under the weight of over 70 years of doctrines, case law, and the politics of the NLRB and that new concepts and rules will be needed to support and protect the variety of ethnic, religious, and other groups and organizations advocating for worker rights that are now present and active in communities and labor markets across the country.48 Opening up the traditional NLRA doctrines to allow these newer actors to find their appropriate roles represents a new frontier for labor policy, one that could best be explored through a process of experimentation and learning.

2. Supporting new directions for labor-management relations

But we cannot stop there. We must do more to ensure what the vast majority of workers want—a positive and cooperative workplace environment in which they can fully use and further develop their skills and engage with each other and their supervisors in efforts to improve services and increase productivity and innovation. This type of high-trust workplace is critical to the success of knowledge-based business strategies and a knowledge-driven economy.

It is not surprising that the OECD economies that perform best and are considered the most competitive in the world economy are ones that have achieved and sustained a high level of unionization and a high level of cooperation between labor and business.49 Achieving this in America will require a change in mindset for labor policy. New forms of employee voice and participation will need to be encouraged that help build high trust, innovative, and productive employment relationships.

There are multiple ways to do this. Some American companies and unions have built labor-management partnerships to promote and support this type of high trust relationship. The evidence is that employees prefer these to traditional arm's-length or adversarial labor management relationships. At Kaiser Permanente, for example, over 70% of union members—nurses, medical technicians, and service staff—agree that their partnership model is preferable to the old adversarial model it replaced.50 Yet these partnerships have proved fragile over the years in large part because they are not supported by national policies or championed sufficiently by employers.

Indeed, a recent NLRB decision would undermine these types of partnerships by taking away collective bargaining and union rights from charge nurses, professionals who work side by side in teams with other front line nurses and health care professionals to deliver health care in a modern, safe, and high-quality way.51 If applied across the board in other industries, this decision would not only strip an estimated 8 million employees of their right to join a union, it would drive a wedge between those who need to work together in improving productivity and service quality. The NLRB's decision should be repealed, if not by the NLRB then by Congress. More generally, it is time for labor policy makers and regulators to update their thinking and understanding of how work is carried out in today's workplaces.

Twentieth century labor policies and NLRB decisions like the one involving charge nurses were designed on an assumption that labor-management relations would be adversarial and therefore union and employee rights and influence had to be limited to a restricted scope of issues so management could remain free to make the big strategic decisions needed to run the enterprise. Not surprisingly, we got what we asked for. Labor relations were largely adversarial, with management resisting efforts by unions to gain a voice in the key decisions affecting the long-term security of the workforce or the direction of the enterprise and with unions combating those management efforts.

This adversarial model now needs to be replaced by a forward-looking model that unleashes employee innovative potential and desires for a more cooperative but meaningful role in shaping their workplaces and contributing to organizational performance. While there is no clear-cut recipe for achieving this objective in the United States, especially if American managers are intent on avoiding or undermining all forms of independent worker voice, it is time to support experiments that test some of the alternatives that have been suggested by various labor policy experts.

These alternatives can include: minority representation and consultation where no formal bargaining unit yet exists; joint committees focused on specific issues such as safety and health improvement and/or monitoring of labor standards; broad-based consultative and information sharing structures and processes similar to European works councils; worker representation on corporate boards; and industry or regional councils to promote high-road business and employment strategies. None of these alone can substitute for the basic labor law reforms and the revitalized system of collective bargaining called for above. But all are worthy of experimentation and testing as part of a policy aimed at encouraging the forms of employee voice and labor management dialogue and problem solving needed to fit the diverse needs of today's workforce and a knowledge-driven economy.

The void in constructive dialogue between labor and business leaders is especially evident at the national level. Throughout our history, government and private sector leaders have created forums to discuss problems of national importance and to build personal and professional relationships that could be called on to solve problems or to respond to national crises. The National Policy Association, the Collective Bargaining Forum, and the Work in America Institute were examples of forums that served these purposes in recent years.52 All, however, have been disbanded. It is not surprising, therefore, that unlike nearly all prior national crises, government leaders did not call on business and labor to work with them to respond to events such as the September 11 attacks and Hurricane Katrina. Our democracy and our national security are weakened by the lack of a national level labor-business network of leaders who can mobilize their resources and work together in response to such events. Rebuilding this capacity should be a priority for labor policy leaders.

In short, labor policy should endorse and support labor management partnerships and actively work with industry and labor to test new ways of working together at the firm, community, industry, and national levels of the economy so that so that worker voice once again becomes the norm, not the exception, in the 21st century American economy.

For all these economic, social, and democratic reasons, a labor movement revival and the labor law reforms that could make it possible are essential to reversing the direction of the country, improving living standards, and restoring the American Dream. But the revival will only happen and the next generation unions and professional associations will only be effective if their strategies for recruiting, retaining, and representing their members are updated to fit the needs and aspirations of today's workforce and the features of today's economy.

3. Building the next generation unions

The vast majority of American workers want a voice at work. As noted above, today more than 50 million workers indicate they would join a union if they had the chance to do so. Over 70 million workers indicate they want a direct voice over how they work, how to get the training and continued education they need to be productive and marketable, how to improve the quality of services they provide their customers, patients, students or clients, and how to ensure their employers adopt business strategies capable of protecting their jobs for the long run.

Meeting these expectations will require the policy reforms outlined above and considerable innovation on the part of unions and professional associations. Leaders of the next generation labor movement will have to find new ways to recruit and retain members and draw on new sources of power to meet worker expectations. Too often unions are viewed as a strategy of last resort to be turned to only when management violates workers' trust. By then it is often too late for those workers who have left these jobs in frustration.

4. New approaches to recruitment and representation

A modern recruitment and retention model must begin by engaging workers very early in their careers. It must make a lifetime commitment to representing them and meeting their needs regardless of where they work. Membership should be for life, not for the life of any particular job. This is especially important for recruiting and serving the needs of women who move in and out of the paid labor force at different stages of their family life cycles and are more likely to need access to educational and training updates and information on alternative job opportunities. Moreover, the initial decision to join a union or professional association should be neither a high-risk venture nor an act of desperation but a natural and expected part of pursuing a career and establishing a network needed to advance and be secure in today's uncertain labor markets.

Unions are experimenting with a variety of ways to organize and recruit members in these new ways. Working America is a new community-based recruiting strategy that has attracted over 1 million members to advocate for "good jobs, affordable health care, world-class education, secure retirements, real homeland security, and more."53 Working Today is an organization that provides freelancers, independent contractors, and temporary workers access to health and disability insurance and other portable benefits and networking contacts that help them move from job to job.54 Across the country from California to Illinois to Massachusetts, unions are working to provide representation and bargaining rights for child care and home health care workers who too often are excluded from coverage under labor and employment laws and thus suffer from chronic low wages and insecurity.

In many communities local unions are also working in coalitions with a variety of religious, ethnic, and immigrant groups to achieve living wage standards and to address the full range of housing, health care, and educational challenges so many working families face today. Worker centers that mobilize union and community leaders to meet the family, health, and employment needs of those who otherwise lack a voice and representation at work and in political affairs have been established in over 80 cities.55 These and other innovative efforts like them need to continue to expand to recruit and represent working families across the full socio-economic spectrum.

In recognition of the failure of labor law to protect workers' rights to organize under the established NLRB election procedures, unions are increasingly turning to alternative approaches involving a mix of strategies to neutralize virulent employer opposition to workers' organizing efforts. Among these are the well-known Justice for Janitors campaigns that have proven successful in organizing building service employees in a number of cities and similar efforts by hotel workers.56 These strategies target regional labor/product markets (rather than single employers) and seek to bring the public into the process by publicizing the issues at stake for low-wage workers and the possibilities union representation offers for improving their wages, access to training and development, and for working in partnership with local employers. Shedding public light on efforts of workers to exercise their rights to organize is an important and necessary step in building awareness and broader support for restoring workers' voice and building a new social contract.

Conclusion

Beyond the architecture: building relationships that work

These specific policy initiatives and institutional reforms are a start in securing a new social contract for the 21st century. They fit together to provide an architecture for an integrated, family-centered labor market policy that matches the needs of today's workforce, families, and economy.

But more is needed than these specific policy and institutional reforms. Putting them to work requires leadership that mobilizes the collective strengths of business, labor, and community leaders around a shared vision for how to build and sustain a productive and innovative knowledge-based economy and an employment system that supports strong families and thriving communities.

Taking the actions needed to update and modernize labor market and employment policies and institutions along the lines proposed here would go a long way toward overcoming America's divisions, restoring trust and faith in government and private institutions, and building a modern social contract for America's families and the economy.

Ultimately, it is a question of what kind of America we want. If we want an America in which hard working families share in the fruits of their efforts and in which the American Dream is not merely a slogan but a lived reality, we must act now. By moving in the directions outlined above, we can reverse the direction of the country and restore faith and hope in the American Dream for our children and ourselves.

— Thomas Kochan is the George M. Bunker Professor of Management at the MIT Sloan School of Management and co-director of the MIT Workplace Center. His most recent book is Restoring the American Dream: A Working Families' Agenda for America (MIT Press 2005).

— Beth Shulman is a consultant and the author of The Betrayal of Work: How Low-Wage Jobs Fail 30 Million Americans (The New Press 2003).

For a more in-depth treatment of the ideas presented in this briefing paper, see the above-mentioned works by the authors.

Endnotes

1. George W. Bush, Economic Report of the President, 2004, p. 4.

2. More specific discussion of this policy issue will be found in the companion EPI Agenda for Shared Prosperity forthcoming report on full employment.

3. ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work and Its Follow-Up: Adopted by the International Labour Conference at the86th Session, Geneva, June 18, 1998, Congressional Record, June 23, 1998; International Worker Rights-A Human Face for the Global Economy, a Report by the United Nations Association of the United States of America, National Capital Area Task Force on Worker Rights in the Global Economy, November 1999.

4. See Jeff Faux's Globalization That Works for Working Americans (2007), EPI's Agenda for Shared Prosperity Briefing Paper, for more comprehensive suggestions for ensuring that global policies benefit hard-working Americans.

5. Jared Bernstein and Isaac Shapiro, Buying Power of Minimum Wage at 51-Year Low, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and Economic Policy Institute, June 20, 2006.

6. See David E. Card and Alan B. Krueger, Myth and Measurement: The New Economics of the Minimum Wage. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

7. Paul K. Sonn, Citywide Minimum Wage Laws, Economic Policy Brief, Brennan Center for Justice, New York University Law School, May, 2006.

8. Health Care and Pensions, Economic Policy Institute, September 2, 2006.

9. Health Care and Pensions, Economic Policy Institute, September 2, 2006.

10. Larwence Michel, Jared Bernstein, and Sylvia Allegretto, The State of Working America, 2006/2007. An Economic Policy Institute Book. Ithaca, N.Y.: ILR Press, an imprint of Cornell University Press, 2007, p. 236.

11. Paul Osterman, Securing Prosperity, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999, p.42.

12. Jacob S. Hacker, Health Care for America, Agenda for Shared Prosperity Briefing Paper #182, Economic Policy Institute, 2007.

13. See for example Teresa Ghilarducci, Guaranteed Retirement Accounts: Towards Retirement Security, Economic Policy Institute Shared Prosperity Project, draft, January, 2007.

14. Unless otherwise cited, the family and labor force numbers cited here are taken from Employment Characteristics of Families in 2005, Bureau of Labor Statistics News Brief, April 27, 2005.

15. The State of Working America 2006/2007, p. 89.

16. The State of Working America 2006/2007, p. 90.

17. Lotte Bailyn, Robert Drago, and Thomas Kochan, Integrating Work and Family Life. MIT Sloan School of Management, 2001, p. 12.

18. See Jody Heymann, The Widening Gap: Why America's Working Families Are in Jeopardy and What can be Done About It. New York: Basic Books, 2000; Jane Waldfogel, "Work-Family Policies," in Harry J. Holzer and Demetra Nightingale Smith (eds.) Reshaping the American Workforce in a Changing Economy, Washington, D.C.: The Urban Institute Press, pp. 273-92.

19. See Heidi Hartmann's EPI Agenda for Shared Prosperity project White Paper for a more in depth discussion of ways to provide these services.

20. Waldfogel, "Work-Family Policies," p. 287.

21. Ross Eisenbrey, Federal Support for Employment and Training Services Dwindles, Economic Snapshot, Economic Policy Institute, December 6, 2006.

22. Peter Auer, In Search of Optimal Labour Market Institutions, Geneva: International Labour Organization, 2006.

23. Paul Osterman, "Employment Training Policies: New Directions for Less-Skilled Adults," in Reshaping the American Workforce in a Changing Economy, pp. 119-54.

24. For an overview of the structure of government employment and training programs, see Burt S. Barnow and Demetra S. Nightingale, "An Overview of U.S. Workforce Development Policy," in Reshaping the American Workforce in a Changing Economy, pp. 25-37.

25. OECD Employment Outlook, 2006: Boosting Jobs and Incomes. http://www.oecd.org/els/employmentoutlook.

26. Auer, "In Search of Optimal Labour Market Institutions."

27. Lori G. Kletzer and Howard Rosen, Reforming Unemployment Insurance for the 21st Century Workforce, Hamilton Project Discussion Paper, September 2006, p. 10.

28. Maurice Emsellem, "Innovative State Reforms Shape New National Economic Security Plan for the 21st Century," The National Employment Law Project, December 2006.

29. For a further discussion of proposals for unemployment compensation reform, see Emsellem, "Innovative State Reforms Shape New National Economic Security Plan for the 21st Century."

30. John Schmitt, "The rise in job displacement: 1991-2004," Challenge, Vol. 47, November/December 2004, pp. 46-68.

31. For a more complete discussion of policies for realigning corporate behavior and objectives with the public's interests, see the forthcoming Agenda for Shared Prosperity companion Companion Briefing Paper, Restoring Public Purpose to the Private Corporation, by Ronald Blackwell and Thomas Kochan, Economic Policy Institute (Draft 2006).

32. See, for example, Margaret M. Blair and Lynn A. Stout, "A team production theory of corporate law," Virginia Law Review, 1999, Vol. 85, pp. 247-328.

33. See, for example, Casey Ichniowski, Thomas Kochan, David Levine, Craig Olson, and George Strauss, "What Works at Work?" Industrial Relations. 1996, Vol. 35, No. 3, pp. 1-19.

34. Wal-Mart and Costco business and employment strategies compared in Charles Fishman, "The Wal-Mart effect and a decent society: who knew shopping was so important," and Wayne F. Cascio, " Decency means more than ‘Always Low Prices': a comparison of Costco to Wal-Mart's Sam's Club, The Academy of Management Perspectives, Vol. 20, No. 3, August, 2006, pp. 6-37.

35. Jody Hoffer Gittell, The Southwest Airlines Way. New York: McGraw Hill, 2003.

36. Jody Hoffer Gittell, Andrew von Nordenflycht, and Thomas Kochan, "Mutual gains or zero sum: The effects of airline labor relations on firm performance," Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 57, January 2004, pp. 163-80.

37. Hirsh Cohen, "Studies of industries and their people," Perspectives on Work. Vol. 2, No. 1, 1998, pp. 13-17.

38. Lawrence Mishel with Matthew Walters, How Unions Help All Workers, Economic Policy Institute Briefing Paper, August 2003.

39. Union Status and Employment Based Health Benefits, Economic Benefits Research Institute Note 26, No.5, May 2005, p. 427.

40. The failures of labor law are documented in Fact Finding Report of the Commission on the Future of Worker Management Relations. Washington, D.C.: Departments of Commerce and Labor, 1994.

41. 2005 Report of the National Labor Relations Board, Table 4, p. 116.

42. John Schmidt and Ben Zipperer, "Dropping the Ax: Illegal Firings during Union Organizing Campaigns, Center for Economic and Policy Research, January 2007.

43. John Paul Ferguson, The Eyes of the Needle: Surviving Union Recognition Campaigns, MIT Institute for Work and Employment Research Working Paper, April 2006.

44. Kate Bronfenbrenner, "Employer Behavior in Certification Elections and First Contracts: Implications for Labor Law Reform," in Sheldon Friedman, Richard Hurd, Rudy Oswald, and Ronald Seeber, (eds.), Restoring the Promise of American Labor Law, Ithaca: Cornell/ILR Press, 1994, pp. 75-89.

45. Adrienne Eaton and Jill Kriesky, NLRB Elections Versus Card Check: Results of a Worker Survey, Rutgers University School of Management and Labor Relations, 2006.

46. See Seymour Martin Lipset and Noah M. Meltz, The Paradox of American Unionism, Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell/ILR Press, 2004.

47. See, for example, Richard B. Freeman and Joel Rogers, What do Workers Want? Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell/ILR Press, 1999; Seymour Martin Lipset and Noah Meltz, The Paradox of American Unions, Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell/ILR Press, 2004.

48. See, for example, Cynthia L. Estlund, "The ossification of American labor law," Columbia Law Review, Vol. 102, 2002, pp. 101-83.

49. Peter Auer, In Search of the Optimal Labour Market Policies.

50. Adrienne Eaton, Saul Rubinstein, and Thomas Kochan, Dynamics of a Union Coalition in a Labor Management Partnership, Rutgers University School of Management and Labor Relations, 2006.

51. Oakwood Healthcare Systems, NLRB, 2006.

52. See for example a report of the Collective Bargaining Forum written and endorsed by a group of corporate chief executives and union presidents: Labor-Management Commitment: A Compact for Change. The Collective Bargaining Forum, Distributed by the U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Management Relations and Cooperative Programs, Report No. 141, 1991.

53. www.workingamerica.org.

54. www.workingtoday.org

55. Janice Fine, Worker Centers: Organizing Communities at the Edge of the Dream, Ithaca: Cornell University Press and Economic Policy Institute, Washington D.C, 2006.

56. Christopher L. Erickson, Elizabeth Fisk, Ruth Milkman, Daniel J.B. Mitchell, and Kent Wong, "Justice for Janitors in Los Angeles: learning from three rounds of negotiations," British Journal of Industrial Relations, Vol. 40, 2002, pp. 543-67. See also, http://www.seiu.org/property/janitors/.

Download print-friendly PDF version ![]()

Copyright © 2010 Economic Policy Institute. All rights reserved. Contact webmaster@epi.org.