|

February 22, 2007 | EPI Briefing Paper #182

DO WORKERS STILL WANT UNIONS?

MORE THAN EVER

By Richard B. Freeman

Download print-friendly PDF version

In the mid-1990s, the Worker Representation and Participation Survey (WRPS) of U.S. private sector workers documented a large gap between the kind and extent of workplace representation and participation that U.S. workers had and the kind they desired (Freeman and Rogers 1999 and 2006). The WRPS revealed that this sizable representation/participation gap spanned diverse groups of workers (men and women, different races, skilled and unskilled, etc.) and work issues (compensation, supervision, training, availability of information on firm plans, use of new technology, etc.). Given a choice between a union and no representation, 32% of nonunion workers reported that they would vote for a trade union in a representation election; while 90% of unionized workers said they would vote for their union in a new election. In the sample as a whole, 44% of workers favored union representation. Even among those who did not seek union representation and collective bargaining there was a large group who desired representation through worker committees that met regularly and discussed matters with management.

Putting aside the particular form of representation that workers favored, the main finding of the survey was that the vast majority of workers—85% to 90%, depending on the particular questions—wanted a greater collective say at the workplace than they had. Moreover, most workers thought that greater representation and voice to employees at their workplace would be good for their firm as well as for them.

In the decade since the WRPS, union representation in the private sector fell from 11.3% to 7.4%,1 while the country has done nothing to deliver to American workers any other form of worker organization to deal with management at their workplace. Has union organization fallen because an increasing proportion of workers no longer want union representation? Or do an increasing proportion of workers want unionism than in the past but cannot obtain it under current labor market and institutional realities?

This briefing paper reviews what post-WPRS opinion surveys tell us about what workers want in the form of workplace representation in the 2000s and compares what American workers say about their representation and participation with what workers say about representation and participation in the other advanced English-speaking countries—Canada, United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia, and New Zealand. The analysis is based on the 2006 updated version of What Workers Want (Freeman and Rogers 2006) and the forthcoming volume What Workers Say (Peter Boxall, Richard B. Freeman, and Peter Haynes 2007), which compares representation and participation in the six advanced English-speaking countries. There are five key findings:

1. Workers today want greater say at their workplace as much or more than in the 1990s. Workers continue to want to have much greater say at the workplace than the U.S. labor relations systems gives them.

2. Workers want unions more than ever before. The proportion of workers who want unions has risen substantially over the last 10 years, and a majority of nonunion workers in 2005 would vote for union representation if they could. This is up from the roughly 30% who would vote for representation in the mid-1980s, and the 32% to 39% in the mid-1990s, depending on the survey. Given that nearly all union workers (90%) desire union representation, the mid-1990s analysis suggested that if all the workers who wanted union representation could achieve it, then 44% of the workforce would have union representation. The rise in the desire for union representation since then suggests that the share of the nonunion workforce wanting union representation in 2005 was 53%. These results, in turn, suggest that if workers were provided the union representation they desired in 2005, then the overall unionization rate would have been about 58%.

3. Workers want a workplace-committee form of representation. Three-fourths of workers desire independently elected workplace committees that meet and discuss issues with management, which some see as a supplement to collective bargaining (having both) and some see as useful as a stand-alone mechanism for voice. Very few workers (14%) are satisfied with their current voice at work and seek no changes although another 10% are unsure about what they want.

4. Workers see management opposition as a major reason for their inability to obtain the workplace representation and participation that they seek. The post-WRPS surveys confirm the finding in What Workers Want (2006) that workers are cognizant of management hostility to collective action through unions, and that this weighs heavily in their consideration of unionizing.

5. The gap between what workers want and obtain in representation is greater in the United States than in any other advanced English-speaking country. About one-half the nonunion workforce in the United States desires union representation but does not have it, a union representation gap far larger than the roughly 25% to 35% gap in the other countries.

Workers today want as much or more of a voice in their workplace than they did in the 1990s

The WRPS found substantial gaps between workers’ desire for influence on decisions and their actual influence in several important features of workplaces. The greatest gaps were for bread-and-butter issues relating to benefits and pay, followed by training issues. The smallest gap was between what workers wanted and had in deciding how to organize their work, because in that area most had substantial independence.

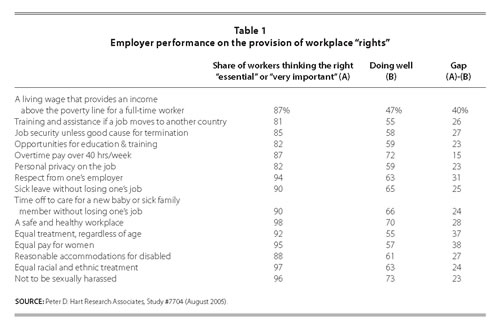

Polls in the 2000s have asked workers how they view employer performance on these and related workplace issues. A 2001 Peter Hart and Associates poll asked how important different workplace “rights” were, and used the WRPS design of asking workers to rate how employers were doing in providing each of those rights. The poll found substantial gaps between the importance of rights to workers and employer performance (Table 1). While differences in questions make it hard to assess whether the Hart results show larger or smaller gaps than those in the WRPS, the gaps in the Hart survey are large, comparable to those in the WRPS.

To see if workers views changed over time, this study relied on a different Hart question, which the survey asked in 1999 and 2005:

Thinking generally about companies and other employers and the way they treat employees, let me mention some different aspects of work, and please tell me how well employers are doing on each item. Are employers doing very well, doing fairly well, falling somewhat short, or falling very short when it comes to … [different issues].

Table 2 summarizes the responses in terms of the proportion of workers who said employers were doing well or falling short, and the difference between the two responses. In 1999 there were moderate differences between the proportions who report employers doing well and the proportion who report them falling short on most issues: an average of five points for bread and butter issues, and two points for issues relating to work conditions and future opportunities. The biggest gap is 17 points on workplace relations due to the huge number of workers who felt that companies were not sharing profits with them.

The 2005 statistics show an increase in the gap in all categories. The difference between the proportion reporting that employers did well and poorly on the bread-and-butter issues rose on all four items, producing an average gap of -31 points. Fully 70% of respondents in 2005 believed that employers fell short in providing regular cost-of-living raises to employees, up from 52% in 1999. The differences between employers doing well and poorly in the work conditions/future opportunities domain rose more modestly, by an average of -7. The difference between doing well and falling short in workplace relations rose to reach an average of -29 points. Other Hart surveys tell a similar story.

A February 2005 Hart survey asked workers to name one or two aspects of their job on which they would most like to see improvement, and compared the results to those in the 1990s Hart surveys. In both the 2005 and 1990s surveys, 18% of workers cited job security as one of the two areas they wanted to see improvement. Over the same period, the proportion that cited health care benefits rose from 25% to 39% of workers, while the proportion looking for improved wages and salaries increased from 42% to 45%, and the proportion looking for improved retirement benefits rose from 25% to 29%.2 With a slightly changed question, offering options in response—“which one or two … do you feel are the biggest problems facing workplace people today?”—an August 2005 Hart survey gave the following list of top concerns: health care costs (35%), jobs going overseas (31%), rising gas prices (29%), raises that don’t keep up with the cost of living (23%), lack of retirement security (14%), and work schedules interfering with family responsibilities (10%).3 Again, material issues dominate.

In sum, while worker opinions vary across specific issues, the general pattern clearly shows rising gaps between what firms deliver at workplaces and what workers want.

Another way to examine how workers view their relation with management is to ask whether they regard labor-management relations at the workplace as good, bad, or in-between. The mid-1990s WRPS found that 18% viewed relations as excellent, 49% saw them as good, 22% viewed them as only fair, and 7% viewed them as poor (What Workers Want, exhibit 3-2).

From 1996 to 2005, Peter D. Hart Research Associates asked a more nuanced set of questions about the relationship between management and workers.4 The firm asked whether management had too much power compared to workers, workers had too much power compared to management, or if there was a pretty fair balance of power between management and workers. The percentage that said management had too much power increased from 47% in 1996 to 53% in 2005, while those judging the relationship to be a “pretty fair” balance declined from 41% to 36%. Just 7% thought workers had too much power in both periods. In its 2005 poll, Hart used a split sample design, substituting the word “corporations” for “management” for half the sample. For this half, 63% of respondents said corporations had too much power, 28% found that the balance with workers was “pretty fair,” while just 4% thought workers had too much power. The more negative response to use of the term “corporations” probably reflects people’s warmer feelings to management, which consists of real people, than the artificial “person” of the corporation, which is just a legal structure.5

In the wake of the scandals at Enron, WorldCom, and other major companies, confidence in business leadership broadly fell. A 2002 CBS News poll reported that only 27% of the public believed that most corporate executives were honest, compared to 32% who thought that in 1985. Gallup’s Social Series 2005 polls show that less than 7% of the public reported that they were “very satisfied” with the size and influence of major corporations and that 60% wanted the influence of corporations reduced in that year.6

Finally, consistent with these findings, the post-WRPS surveys suggest that workers have a greater desire for increasing their influence on their workplace in the past decade or so. The most cogent evidence comes from the California Workforce Survey conducted by the University of California-Berkeley in 2001-02. This asked workers how important it was to them personally to have more respect and fair treatment on the job and how important it was for them to have more say in workplace decisions. Seventy-five percent of workers in the California survey said that it was very important to have more respect and fair treatment on the job. Fifty-one percent said it was very important, and 38% said it was somewhat important to have more say in workplace decisions. The sum of these last numbers, 89%, exceeds the 63% from the WRPS who wanted more influence.

Workers want unions more than ever before

To assess whether nonunion workers wanted unions, the WRPS asked, “If an election were held today to decide whether employees like you should be represented by a union, would you vote for the union or against the union?” Thirty-two percent of nonunion/nonmanagerial workers said that they would vote for a union—a proportion roughly similar to the proportions of the intention to vote found in surveys in the 1970s and 1980s.7 Ninety percent of union workers said they would vote to keep the union. These two statistics implied a desired rate of private sector unionization of 44% (among nonmanagerial workers in the sample), which was about four times the actual rate of unionization in 1995.

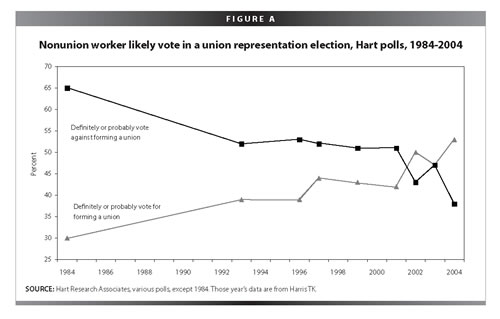

Figure A shows the proportion of nonunion workers who say they would vote for or against a union in polls conducted by Hart Research Associates from 1993 through 2005, supplemented with data from a 1984 Harris poll, which asked the same question. The Harris poll shows that in the mid-1980s, 30% of nonunion workers would vote union in a secret ballot election—a comparable figure to the WRPS estimate (the Hart estimates for 1994 and 1996 of 39% are higher than the WRPS estimate of 32%). What is most striking in the figure, however, is the upward trend in the likelihood of voting for a union since the mid-1990s. In 2002 the proportion of workers who said they would vote for a union rose above the proportion that said they would vote against a union for the first time in any national survey: a majority of nonunion workers now desire union representation in their workplace. At the same time, the proportion of union members who say they would vote for their union has remained extraordinarily high,8 so this is not simply a general rejection of the workplace status quo.9 Together, these results suggest that if workers were provided the union representation they desired in 2005 then the unionization rate would be about 58%, up from the 44% estimated from the mid-1990s WRPS.10

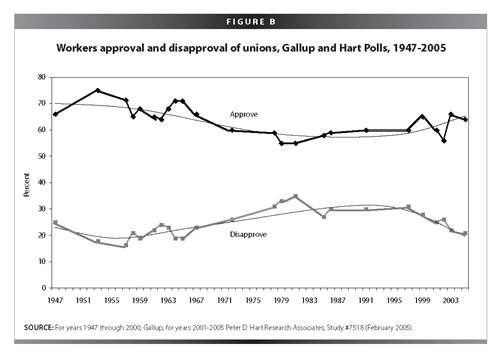

Is it possible that the finding of an increased desire of workers for unions is some artifact of the Hart surveys? To see if this might be the case, What Workers Want examined data from Gallup and Harris polls that ask the public about their attitudes toward unions more generally. The longest standing question about unions is “do you approve or disapprove of labor unions” from Gallup. Figure B gives the results from this question from 1947 to 2005. The proportion of Americans that approve of unions always exceeds the proportion that disapproves. From 1947 through 1981, however, the difference between the proportion approving and disapproving declined from about 40 percentage points to about 20 percentage points. Since then, the trend decline has reversed, with the proportion of the public disapproving of unions dropping sharply from 1995 through 2005. In 2005, the difference between the proportion approving and disapproving reached 43 points, a bit larger than it was in 1947. This is consistent with a large increase in workers wanting to unionize.

Gallup surveys have also asked whether people want unions to have more or less influence on social outcomes. The responses also show that a rising proportion want unions to have more influence. In 2005, 38% of persons wanted unions to have more influence, 30% wanted unions to have less influence, and 29% wanted their influence to stay about the same. By contrast, in 1999, 30% wanted unions to have more influence—eight points less than in 2005; while 32% wanted unions to have less influence and 36% wanted their influence to stay about the same. But, indicative of the problem of the U.S. labor system, in 2005, 53% of adults said that they expected that unions would become weaker over time—a higher percentage than in the 1999 poll, where 44% said they believed unions would be weaker.11

Workers want a workplace-committee form of representation

The WRPS went beyond the standard “would you vote for a union in a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) election?” to ask workers about their preferences among a wider choice of institutions for representing their interests to management. The survey found that, given a choice between a union and joint management employee committees that would meet and discuss problems, 52% of workers chose the workplace committees, 23% chose unions, while the remaining workers chose increased legal protection or opposed any independent organization.12

To better understand what employees mean when they say they want a workplace committee form of representation, the WRPS asked employees what their ideal employee organization would look like. The committees that respondents had in mind are quite different from the management-dominated committees that would have been permitted by the TEAM Act Congress considered a decade ago. A majority of non-management employees favored having elected employee representatives, less than a quarter favored volunteer representatives, and less than 10% favored allowing managers to select the representatives. Equally noteworthy, a majority of workers favored giving an arbitrator the power to make final decisions in cases of conflict between the employees and management.

Subsequent polls confirm that workers see these institutions as attractive. Figure C shows that in each year in which the Hart survey asked workers whether they supported an association of workers that was not a union to represent the interests of the employees and meet regularly with management, nearly 40% said they would definitely vote for the association. Approximately another 40% said they would probably vote for it, compared to just 18% who were either definitely or probably against it. In the 1997 survey, Hart asked the workers who said they wanted an employee association but not a union in what ways workers wanted this employee association to be different from a labor union. Ten percent said they did not want to pay union dues, and 7% said because the group would not be as powerful or have as much control as a union. But the majority of reasons given reflected the desire to have a voice with management that avoided confrontation: 19% favored an association to work as a group with one voice with less antagonism (than a union); 16% said they wanted the group to stand by employees; and 14% referred to better communication. Thus, about half of those who favored an association over a union wanted an independent voice at the workplace without collective bargaining, irrespective of dues and concern over union failings.

Combining the responses of workers toward unions and an employee association, Table 3 decomposes workers into the four categories, depending on whether they favor unions and associations, just one or the other institution, or neither. The largest group consists of the 39% of workers who favor unions and an employee association, which makes them the strongest supporters of collective voice. The second largest group consists of the 35% of workers who want an employee association but not a union. Along a variety of dimensions, the workers who oppose unions but would vote for an association look very different from traditional union supporters. They are more likely to be Republican, to be white-collar workers, to have higher incomes, and to be white than persons who say they would vote union.13 In total, 76% of workers want a significant institutional change that would give them a voice at the workplace, either union representation, a workplace committee, or both. Only 14% of workers are satisfied with the status quo, meaning they are the opposed to either form of collective voice.

Workers see management opposition as a major reason for their inability to obtain the workplace representation and participation that they seek

So what is stopping U.S. workers from obtaining the representation and participation that they want in the workplace? The post-WRPS surveys confirm the finding in What Workers Want that workers are cognizant of management hostility to collective action through unions, and that this weighs heavily in their consideration of unionizing. A 2005 Hart survey found that 53% of workers believe that “employers generally oppose the union and try to convince employees to vote no” in NLRB elections, while less than half as many (26%) think that “employers generally take no position and let the employees decide on their own.”14 Another Hart survey found that approximately one in five (22%) thought that employers used specific anti-union tactics (ranging from requiring employees to attend anti-union presentations on company time to firing union supporters) “all the time or fairly often,” that 25% thought employers used the tactics just sometimes, that 23% thought employers used the tactics not very often, while 10% thought the employers never used the tactics (18% were unsure).15 Although it is difficult to compare the qualitative survey responses to quantitative estimates of the extent to which firms use the tactics in organizing campaigns, actual use appears to exceed public perceptions.16

The public opposes many of these management practices, the legal tactics as well as the illegal violations of the labor law.17 At various times, unions have tried to harness this opposition to create the kind of public furor that would lead Congress to increase the penalties on employers for committing unfair labor practices during organizing drives. But the union campaigns have not been successful. In the abstract, a large proportion of the public believes that it is important to have strong laws that give workers the right to form and join unions. In a 2005 Hart survey, 50% of the general public said it was very important and 23% said it was fairly important to have such laws.18 But when it comes to placing greater penalties on employers, the proportion of the public who favored adding tough penalties to the law just marginally exceeds the proportion opposed to adding tough penalties. Forty-seven percent of the public said that they approved of changes in the law that would involve tough penalties for violations by employers, 43% disapproved, and 10% were clueless. Even among union members, the proportion favoring tough penalties on employers was just 59%.19 In another survey, Hart reports that approximately one-third of respondents approve of anti-union campaigns compared to a bit over a half who disapprove, and that this division varies by party identification, with Republicans evenly split between approval and disapproval, while Democrats are disproportionately disapproving.20

In 2003, the Hart survey asked a question that illuminates worker concern about employer opposition to unions and the desire of workers for cooperative relations in one swoop. Hart asked respondents which of three factors was the “biggest disadvantage to having a union”: having worse relations between employers and management, being forced to go on strike, and paying more in dues than the union delivers. The biggest factor for the general public, with 38% of responses, was having worse relations between employees and management, followed by being forced to go on strike (29%) and paying more in dues (20%). Among union members, 32% cited worse relations between employees and management as the biggest disadvantage, while 29% cited paying more in dues than the union delivers, and only 18% cited being forced to go on strike.21

The gap between what workers want and obtain in representation is greater in the united States than in any other advanced english-speaking country.

The rate of unionization has been falling in many advanced countries. In European countries like France, Germany, and the Netherlands, falling union density has little effect on the proportion of workers whose wages and working conditions are covered by collective bargaining. This is because these countries have mandatory extension laws that extend union management agreements to all workers and firms in a sector, including those who did not participate in negotiating the agreement. In the English-speaking countries that are closest to the United States, declining unionization invariably means declining coverage by collective contracts as well. How does the gap between what workers want and have in our English-speaking “cousins” compare to that in the United States?

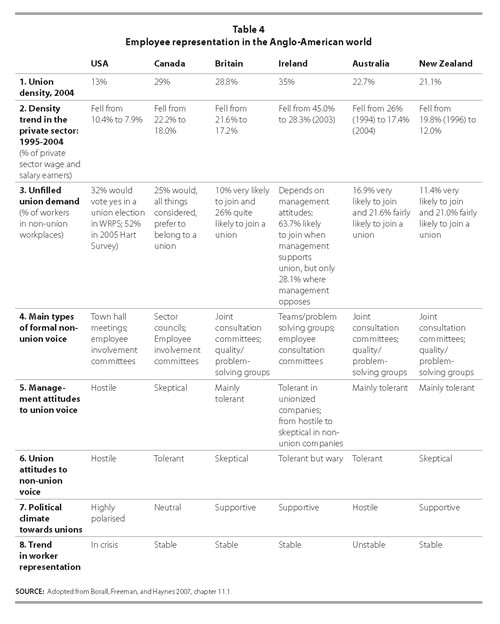

Between 2004 and 2006, a group of economists from the English-speaking countries worked on a joint project to compare the state of worker representation and participation across the Anglo-American world, using variants of the WRPS. Table 4 gives a capsule summary of the findings of this study. Rows one and two show that unionization has declined throughout the Anglo-American world. Outside the public sector, unions are no longer the “default” or natural option in any country.

The country analyses also demonstrate that a sizeable minority of workers want greater influence in the workplace, and that a sizable proportion in all countries have “unfilled demand for unions.” But, in no country does unfilled demand come close to the over 50% gap (e.g., the share of nonunion workers wanting union representation) found in the Hart surveys for the United States in the mid-2000s (Table 4, line 3). Indeed, even the 32% nonunion gap found in the WRPS exceeds the comparable proportions found in other countries.

The collaborative study of employee representation examined alternative forms of labor representation—“formal nonunion voice”—and the attitudes of management toward unions and of unions toward nonunion forms of worker representation. In every country in our study except the United States, public policy allows management to provide alternative forms of representative voice in which workers can discuss their employment concerns (line 4), whereas the United States outlaws such groups. Under U.S. law, employee involvement and related committees discuss productivity and related economic issues that benefit the firm but do not discuss improvements in pay or benefits for workers. Management sets up and disbands committees as it sees fit. Workers do not initiate employee involvement or other committees. Because of the different institutional arrangements, outside the United States, nonunion representative voice now typically complements, rather than substitutes for, union voice and, even where it substitutes, it does so because workers are generally happy with it. The trend to a more diverse set of direct and non-collective bargaining representative voice practices fits with the preferences of many workers.

Rows five through eight of Table 4 summarize the state of voice regulation as of the mid-2000s and the assessment of the expert analysts of the success with which the country delivered to workers the representation or participation they want at the workplace. The desires of workers for representation can be undermined by management’s hostility to unions (row five) as in the United States, which the experts judge to be the only part of the Anglo-American world where management is hostile to unions. In this setting, unions oppose alternative forms of representation (row six). The all-or-nothing, adversarial nature of the U.S. labor relations system gives firms the incentive and tools to defeat union organizing efforts and leads unions to fear nonunion channels of voice as substitutions rather than supplements to collective bargaining. In the other Anglo-American countries, national politics are generally supportive of diversity in employee voice, and labor policies seek to enable, rather than obstruct, union organizing and to let workers decide the fate of trade unions.

As a result, the expert assessment was that U.S. labor laws and institutions, established to secure union voice on a democratic and independent basis, have become the worst case scenario for workers—a system in crisis.

Conclusion

In the mid-2000s, workers see a major gap between the representation and participation they want at the workplace and what they have; the largest proportion ever recorded in survey data express a desire for union representation. Many workers also desire workplace committees that meet and discuss issues with management, some as a supplement to collective bargaining and some as useful even without collective bargaining. Many attribute the absence of mechanisms for workers to discuss issues with management to management opposition to workers speaking out, and the United States has fallen far behind other English-speaking countries in providing alternative modes of employee voice at the workplace. The desire for worker representation revealed in the WRPS survey in the mid-1990s has become even stronger today.

—Richard B. Freeman holds the Herbert Ascherman Chair in Economics at Harvard University. He is also director of the Labor Studies Program at the National Bureau of Economic Research, co-director of the Labor and Worklife Program at Harvard Law School, and a visiting professor at the London School of Economics.

Endnotes

1. See http://www.trinity.edu/bhirsch/unionstats/Union Membership, Coverage, Density, and Employment Among Private Sector Workers, 1973-2006, where the figures are percent of members.

2. See Peter D. Hart Research Associates, Study #7518 (February 2005).

3. Peter D. Hart Research Associates, Study #7704 (August 2005).

4. See Peter D. Hart Research Associates, Study #7518 (February 2005).

5. Consistent with the rising belief that corporations have too much power, in 2002 58% of Americans thought that big business had too much influence on the Bush Administration compared to 22% who thought they had the right amount and 8 % who thought that big business had too little influence. CBS News Poll: Little Faith in Big Biz, July 10, 2002, The Ethics of Big Business, http://www.cbsnews.com/htdocs/c2k/bizback.pdf

6. Gallup’s polls: “Mood of the Nation,” (2005) for business influence; and November Wave 2 (2002) and November Wave 1 (2004) on business executive honesty. A Harris poll with different wording found that 83% wanted to reduce corporate influence.

7. The WRPS 32% for 1995-96 is about the same as the 30% reported in the Harris Poll in 1984 and is comparable to data from other surveys for that period, such as the Michigan quality of work life survey. But, as noted in the discussion of exhibit 3, the Hart survey gives a higher proportion for the mid-1990s than in the WRPS. The survey by Lipset and Meltz (Seymour Martin Lipset and Noah Meltz ) The Paradox of American Unionism: Why Americans Like Unions More Than Canadians Do, but Join Much Less (ILR Press 2004) for 1996 also gives higher numbers than the WRPS.

8. The WRPS reported that 90% of union members said they would vote to support their union if they were asked to vote to keep it or get rid of it in an NLRB election. Only one post-WRPS survey replicated the WRPS design of asking union members how they would vote in an election for union representation. The 2002 California survey found, as we did, that union members would overwhelmingly choose their union again: 86% said that they would vote to keep the union, while 13% were for getting rid of it.

9. But not all recent surveys, however, show such high proportions wanting to unionize as does the Hart survey. A 2005 Zogby poll reports that 36% of nonunion workers were likely to vote union, which is 4 points (13%) above the 32% WRPS estimate for 1994-95 but far below the 53% Hart estimate for that year. Zogby International, The Attitudes and Opinions of Unionized and Non-Unionized Workers Employed in Various Sectors of the Economy Toward Organized Labor, report to the Public Service Research Foundation, August 2005. It is unclear why the 2005 Zogby estimate is so much lower than Hart’s, or Zogby’s own estimate the previous year. Then, on a slightly different question wording – “If you had a choice, how likely would you be to join a union?” – Zogy found that 45% of nonunion workers would likely join one. See Zogby International, Nationwide Attitudes Toward Unions, report to the Public Service Research Foundation, February 2004.

10. For this estimate, I multiply the 87.5% of workers in the U.S. who are nonunion and apply the 53% who said they wanted a union in 2004 and multiply the 12.5% who had a union by 90% and sum the two statistics.

11. See Gallup Poll, “Shift in Public Perceptions About Union Strength, Influence,” August 23, 2005. The polling data vary quite a bit from year to year, so that it is possible the 53% is an aberration. On average over the period though 43% unions were going to get weaker compared to 22% who said they were going to get stronger.

12. Freeman and Rogers, Exhibit 7.4. When the WRPS replaced the union option with “an employee organization that would negotiate with management,” the proportion favoring the joint committees fell to 46% while the proportion favoring bargaining with management rose to 31%.

13. Peter D. Hart Research Associates, Study #6221 (January 2001).

14. Peter D. Hart Research Associates, Study #7518 (February 2005).

15. Peter D. Hart Research Associates, Study #6924 (2003). The question asked: “I’m going to describe some ways that employers might express their opposition to union during union representation elections. For each one please tell me whether you think that employers do this all the time, fairly often, just sometimes, or not very often?” and listed eight tactics.

16. Kate Bronfenbrenner, Uneasy Terrain: The Impact of Capital Mobility on Workers, Wages, and Union Organizing, 2000 (http://www.citizenstrade.org/pdf/nafta_uneasy_terrain.pdf), reports that 92% of private-sector employers order employees to attend closed-door meetings to hear anti-union propaganda; 78% require that supervisors deliver anti-union messages to workers they oversee; half threaten to some shut down if employees unionize; and a quarter fire union supporters.

17. According to Peter D. Hart Research Associates, Study #6924 (February 2003), 77% think employers should take no position in such campaigns and find “unacceptable” a number of common anti-union employer tactics: captive audience meetings (60%); anti-union letters sent to employees’ homes (63%); warning of plant closings or layoffs from a pro-union vote (64%); anti-union literature in pay envelopes (67%); predicting falls in pay or benefits from a pro-union vote (73%); one-on-one meetings with supervisors urging a vote against the union (78%); having security guards closely following pro-union employees at work (85 %); and firing workers for being union supporters (92 %).

18. Peter D. Hart Research Associates, Study #7518 (February 2005).

19. Peter D. Hart Research Associates, Study # 6924 (February 2003).

20. Peter D. Hart Research Associates, Study #6221 (January 2001) and Study # 6924 (February 2003).

21. Peter D. Hart Research Associates, Study #6924 (February 2003).

References

California Workforce Survey. 2002. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California-Berkeley.

Freeman, Richard B, and Joel Rogers. 1999 and 2006. What Workers Want. Ithaca, N.Y.: ILR Press, an imprint of Cornell University Press.

Download print-friendly PDF version

Top of page

|